South Dunedin Future has reached a major milestone with the release of 16 possible adaptation approaches for the area.

1. Protect: ground reinforcements

Ground reinforcement is a preventative method to stabilise soils and reduce liquefaction potential. Methods include densification of the crust or deeper liquifiable soils, crust strengthening, reinforcement, containment by ground reinforcement or curtain walls, and drainage improvements using stone columns or earthquake drums.

2. Protect: groundwater lowering / drainage / dewatering wells

When the sea level rises, groundwater rises and flooding risk increases. This exposes underground structures and networks, building foundations and low-elevation roads to wetter conditions. Options to lower the groundwater could include drainage and dewatering wells. The extent of the groundwater lowering is specific to soil type, groundwater conditions, geology and is limited to above ground surroundings.

3. Protect: land grading

Land grading is also known as land elevation, a flood risk management strategy that involves physically raising the ground level above the floodplain (existing and future). Historically South Dunedin has implemented a “land elevation” technique which has served the area for about 150 years.

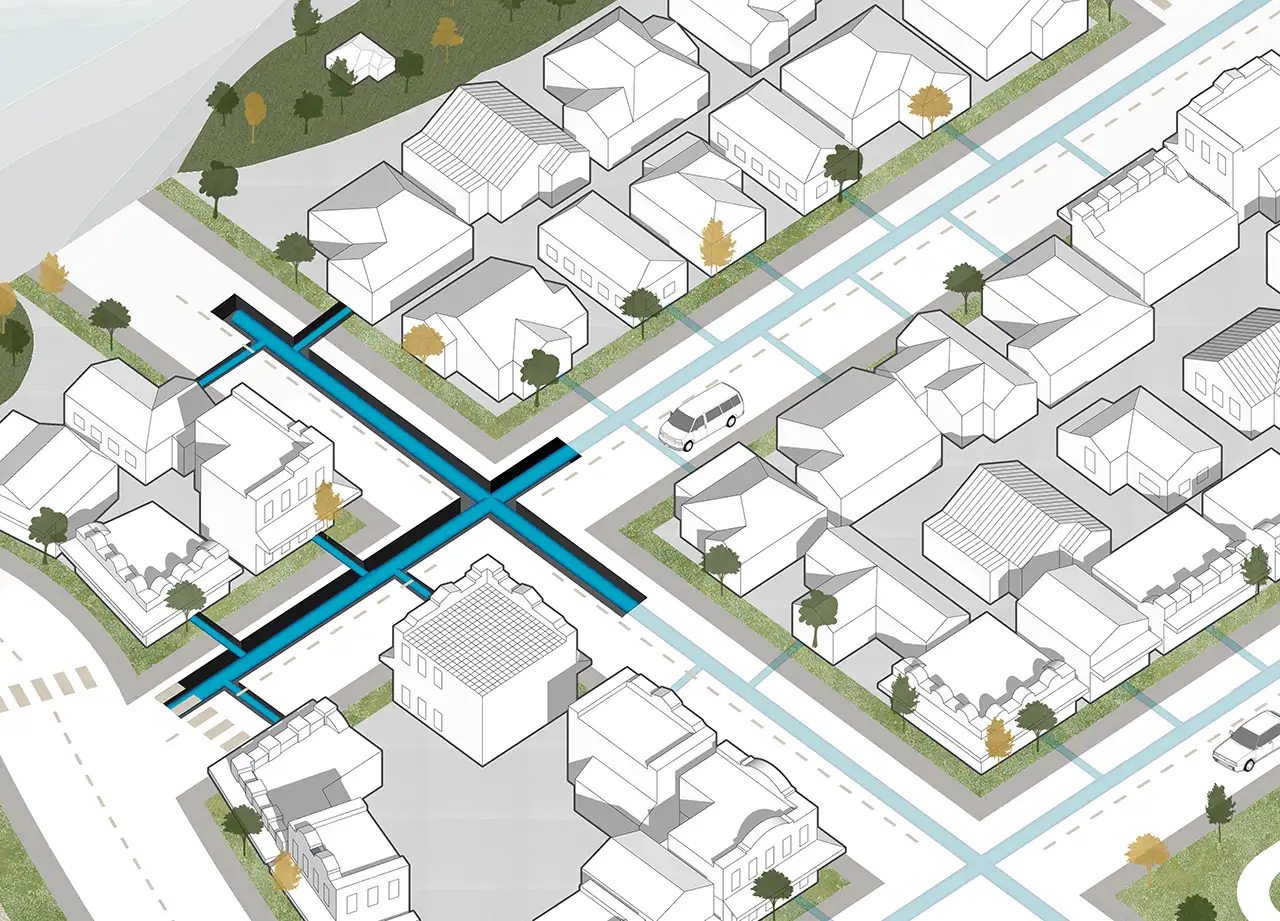

4. Protect: water flow improvements

Water flow improvements involve the enhancement or modification of existing and new drainage systems. This might involve combinations of installing larger pumps and pipes to increase water flow, intercepting and diverting flows upstream, creating engineered channels or canals and/or enhancing stormwater conveyance capacity both overland and through piped networks.

5. Protect: remove wastewater network overflows and cross-connections

Removing wastewater network overflows would avoid wastewater spilling out from gully traps, manholes, or engineered/constructed overflow points when the network has reached full capacity protecting people from health risks associated with flooding. Resolving wastewater network overflows and cross-connections can be achieved by measures such as fixing cracked pipes or manholes.

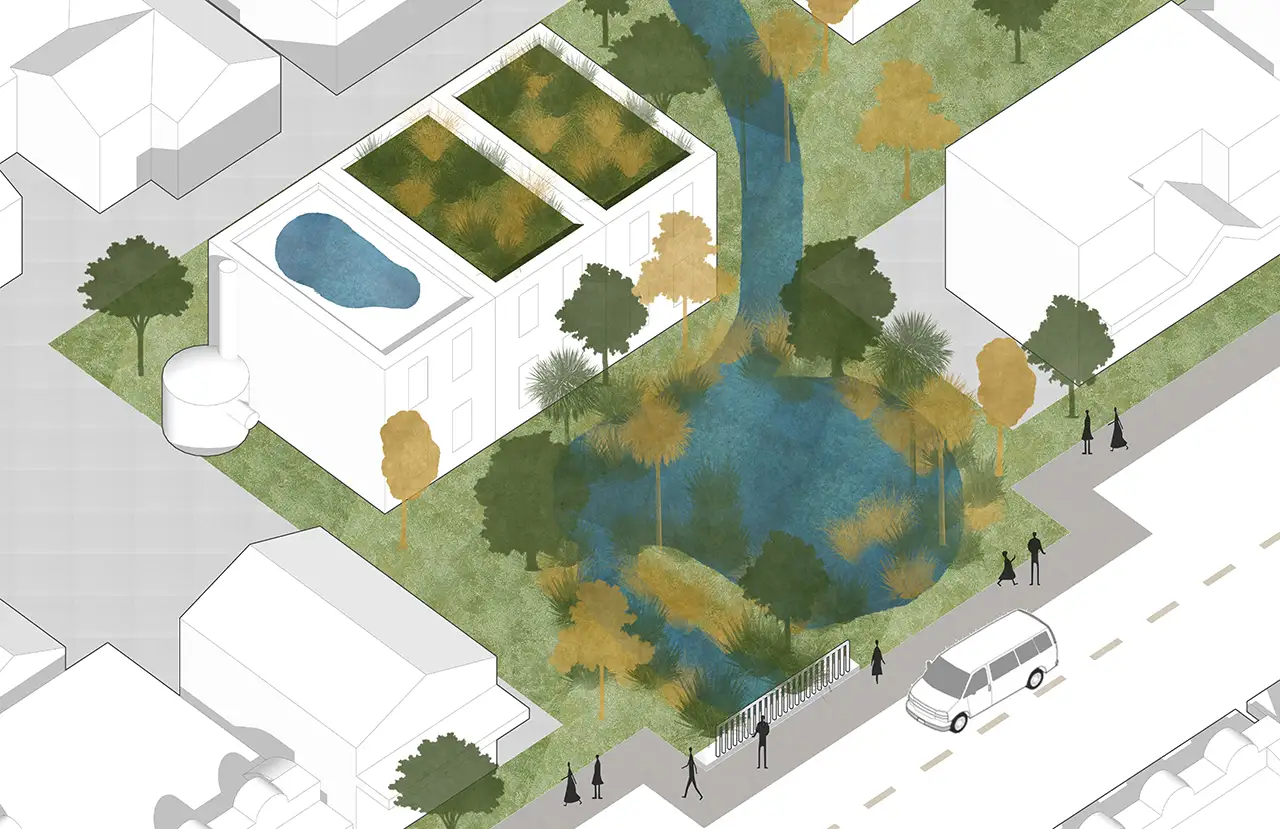

6. Protect: dedicated water storage

Dedicated water storage areas include detention basins, ponds and wetlands that can be located at the coast or inland. They feature a permanent allocation of land or space for water storage, which typically incorporates a permanent body of water and a “live” storage component which fills during storms and is slowly released once the storm has passed. Storage can be on surface or underground.

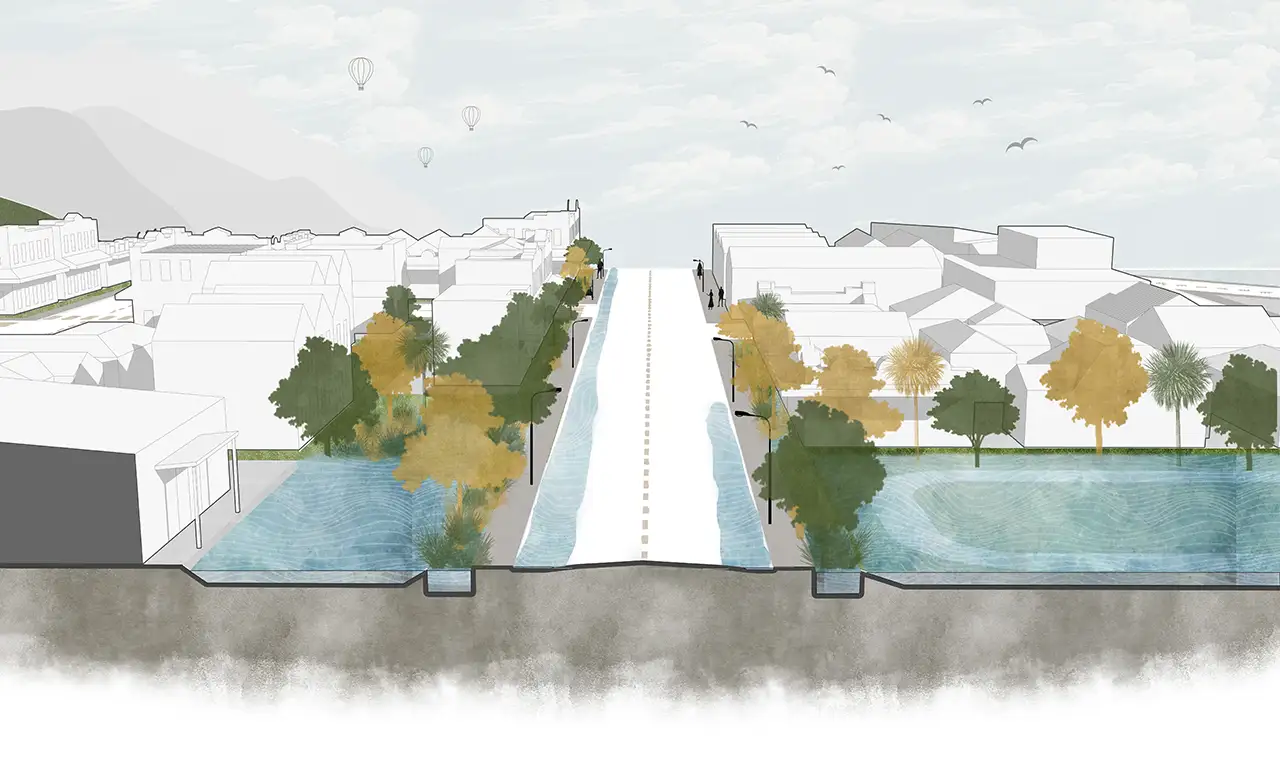

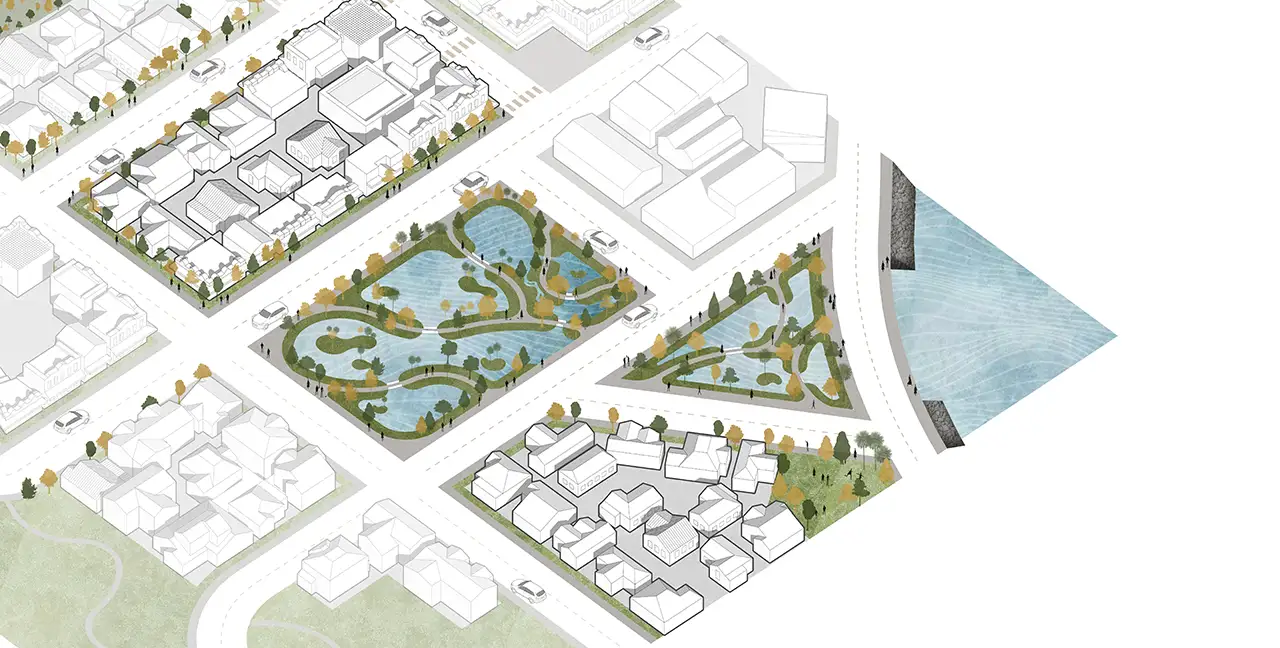

7. Protect: floodable infrastructure

“Floodable infrastructure” refers to open spaces, green spaces (e.g., parks, reserves), carparks, and roads being transformed into intentional temporary flood storage zones or overland flow paths to protect other areas from flooding. There may also be options to store stormwater runoff further upstream as a way to protect areas further downstream in South Dunedin.

8. Protect: increase permeability of ground surface

Increasing permeability of the ground surface improves the receiving environment’s ability to absorb and/or manage excess rainwater, reducing the volume and rate of runoff that would otherwise go through to the stormwater network. This could involve various strategies such as green roofs, reducing impervious area of carparks or other surfaces, introducing rain gardens, bioswales or planting more trees. These elements are often referred to as components of a ‘sponge city’ that soaks in rainwater, filters it, and releases it slowly like a sponge, thereby reducing flooding and regulating water levels.

9. Protect: coastal protection

Coastal protection comprises various tactics aimed at safeguarding coastal areas and can include ‘hard’ engineering options and ‘soft engineering’ options which each have their own strengths and drawbacks. Hard options for coastal protection include sea walls, revetments, berms, dykes, tidal barriers, groynes, breakwaters and flap gates on stormwater networks. Soft engineering options like salt marsh, coastal wetlands, sand placement and dune restoration can be established at the coastal edge to reduce wave energy and surge effects and therefore erosion.

10. Accommodate: behavioural / societal changes

Societal and behavioural changes can help people prepare, respond, cope, and recover from natural hazard events, by learning from past experiences and adapting accordingly. Potential approaches to increase community resilience and understanding of climate hazards include: mental health support, climate hazard safety education and awareness, financial incentives / disincentives (e.g. rates rebates to encourage resilient modifications or increases in insurance cost reflective of increased risk).

11. Accommodate: readiness and response

Readiness or preparedness measures typically refer to the operational systems, capabilities and educational activities that are put in place before an acute event. Response refers to actions taken during or immediately after an emergency event like flood or earthquake. Readiness and response work would typically involve consideration of risk assessment and planning, early warning systems, public education campaigns, emergency response plans, including deploying temporary flood barriers (e.g. sandbags) and providing support services prior, during and immediately after an event.

12. Accommodate: property level interventions

Property level interventions refer to adjustments or modifications that are made directly to individual properties to enhance their resilience against flooding. These could include raising homes, waterproofing first floors, raintanks, flood barriers, or other individual property level interventions. Property level interventions are generally divided into two types. Resistance measures are designed to mitigate the impact of external factors, acting as protective barriers against potential threats, such as bunding or small flood gates preventing flood water from entering a house. Resilience measures focus on strengthening a system’s ability to endure shocks, recuperate, and adjust, underlining its responsiveness and adaptability.

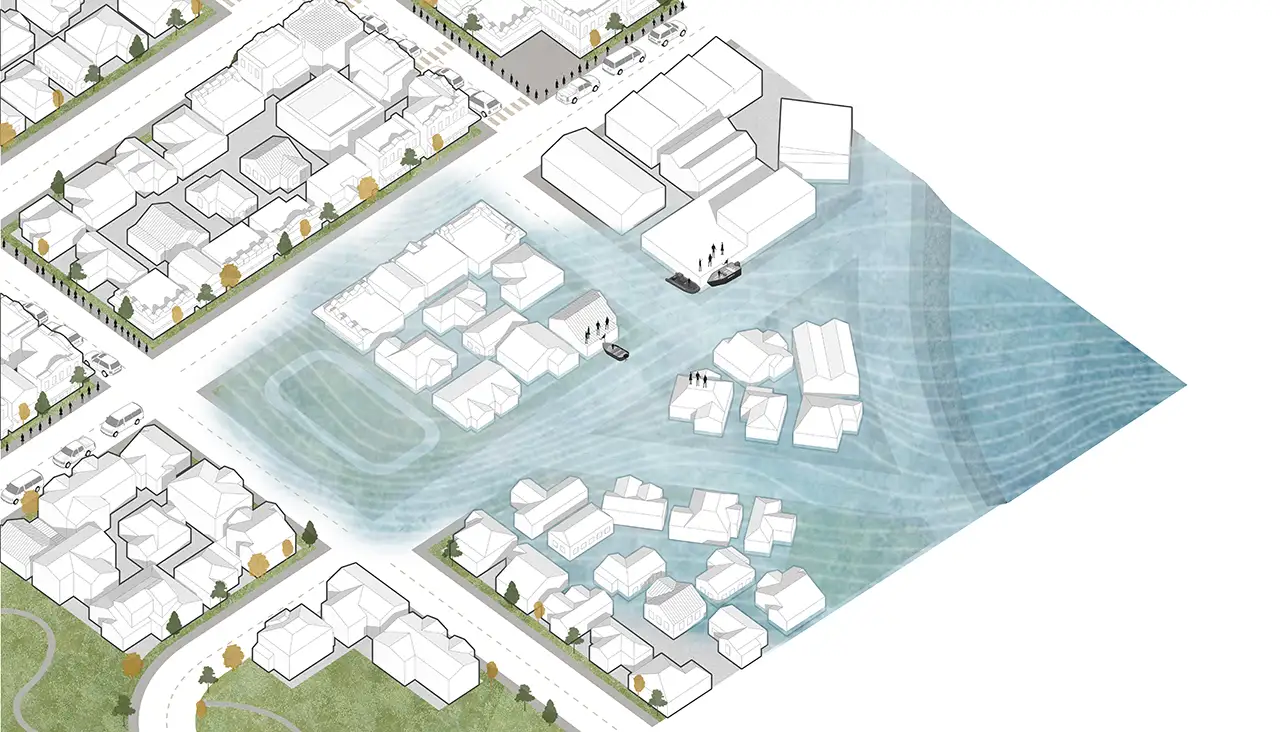

13. Retreat: reactive retreat

Reactive retreat is the withdrawal, relocation or abandonment of private or public assets in response to immediate threats or after damage has already occurred. It involves a more reactive approach where decisions are made in direct response to acute events like storms, flooding, tsunami, earthquakes or rapid erosion. Reactive retreat can include post-disaster buyouts or post-insurance withdrawal buyouts, or emergency evacuations.

14. Retreat: managed relocation

Managed relocation (proactive retreat) is a strategic decision to withdraw, relocate or abandon private or public assets (including land and buildings) before significant damage occurs. It focuses on identifying areas at high or intolerable future risk of natural and climate hazards, thereby minimising long-term risk exposure by transferring people, property and assets away from these areas before the impacts of the hazard are experienced. Managed relocation can take a range of forms which can be phased overtime including: voluntary buyouts on open market, buyouts with climate leases, targeted retreat of built environment or retreat of critical infrastructure from vulnerable site.

15. Avoid: more restrictive building development standards

These approaches involve controls on development to reduce exposure and vulnerability to hazards such as earthquakes and coastal flooding. They may include more restrictive standards, development guides, regional and district plan rules, resource consent conditions, bylaws, urban development or growth strategies to mitigate the impact of a hazard. Planning provisions or building standards may be introduced on matters like building foundations, drainage systems, setbacks, floor heights, flood proofing, individual on-lot water detention and retention, non-permanent structures, land use coverage or reduced consent durations to regulate activities in areas exposed to hazards.

16. Avoid: no new development / redevelopment or change of land use that may exacerbate risk

Restricting development of land uses through planning rules, can prevent further development and, overtime, reduce exposure to hazards. This approach may also identify that an area may not be viable for development in the longer term and change the land use in the district plan to enable retreat. This could involve permitting more development in areas of low risk (through intensification or traditional development including outside of South Dunedin), restricting new development and land use changes in high risk areas, changing land uses to prevent rebuilding, prohibiting landowners from building in flood prone areas all of which could include district plan changes.

❮

❯

About the approaches

The list was created by combining the most promising approaches being used around the world in similar contexts with the 280 ideas collected from people through community engagement in 2023.

The adaptation approaches are grouped according the ‘PARA’ framework (protect, avoid, retreat, accommodate), which is used to identify and explain the types of actions or approaches that might be taken to adapt to the natural hazards and the impacts of climate change.

The approaches range from protection schemes like drainage and water storage to new planning controls and forms of partial retreat.

Some new approaches highlighted include designing open spaces such as roads and parks to be floodable and diverting water from buildings, ground strengthening, building land up and resilience measures such as lifting or waterproofing houses.

None of the approaches have been costed at this early stage because that will depend on the scope, scale and time periods for which they are applied. For instance, raising one house will have a very different cost to that of elevating the land of a number of sections on a block.

Delve into the details

You can view our factsheets for each of the 16 adaptation approaches.

The long list and visual images were developed by Kia Rōpine, a consortium of contractors comprised of engineering services companies WSP, Tonkin & Taylor, and Beca, who are together providing technical support for the South Dunedin Future programme.

You can read about the findings in the Long List of Generic Adaptation Approaches Context Summary Report.

Next steps

In February and March 2024 we will be out engaging with communities, mana whenua and all the many stakeholders to get feedback on the approaches and start narrowing down which ones could be used in which parts of South Dunedin.

There will be a wide range of opportunities over the next two years to consider the issues, understand the approaches and trade-offs, hear what others think and want, and play an active role in the decision-making. In this way, everyone can help shape the area’s future.

Keep in touch and get notice of all our events by subscribing to the email newsletter.