Issue

Accessibility within and between Dunedin’s local centres and the city centre needs to be improved for public transport and active travel modes in order to achieve the Spatial Plan and Transport Strategy vision for thriving and resilient centres, linked by a low carbon transport system.

Course of action

Improve the connections within and between Dunedin’s local centres so that they become highly accessible by active travel modes and public transport, and improve the road environment within centres to create safe, pleasant, people-friendly places.

Outcomes

- Increased connectivity between Dunedin’s central city and local centres, and between local centres, for cycling and public transport.

- Increased proportion of Dunedin’s population live within a 10-minute walk of a local centre or high frequency bus route.

- Improved walking and cycling connectivity to local centres and the city centre from surrounding residential areas, to support thriving community hubs.

- Reduced negative effects of traffic passing through local centres.

Goal

Injury crashes have reduced by 20% (compared to 2013 levels) in Dunedin’s centres by 2024.

Strategic approach

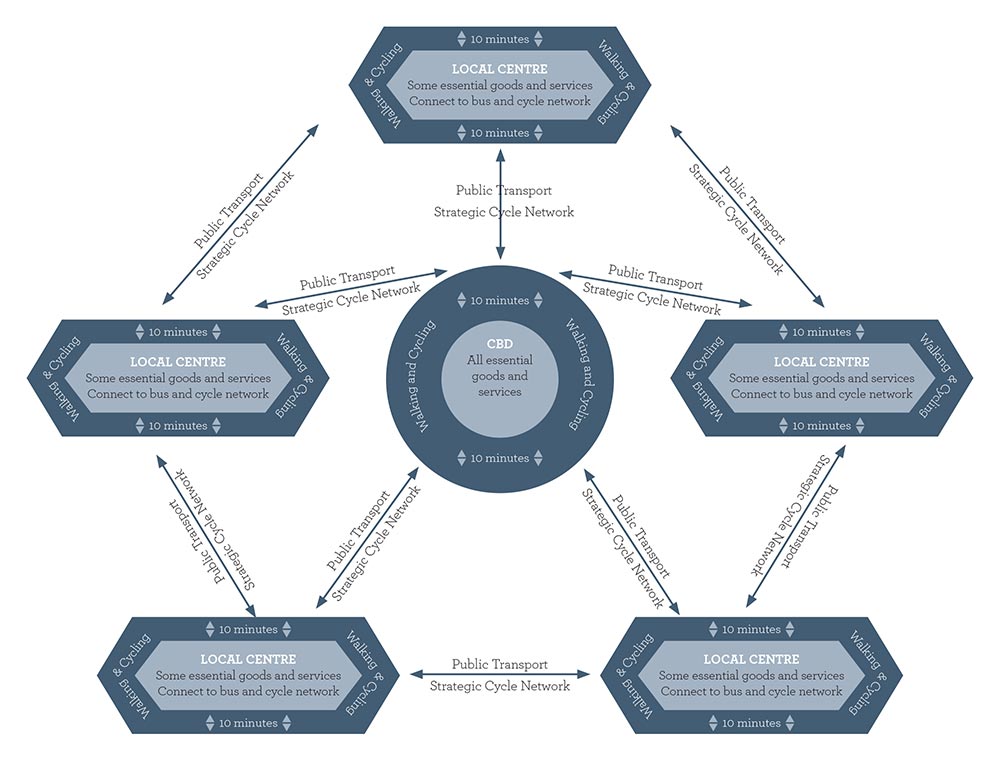

The Social Wellbeing Strategy recognises the importance of people being connected to the places they need to go by safe, affordable and user friendly transport options, whilst the Spatial Plan commits Dunedin to developing as a compact city, organised around an integrated network of hubs and centres. In terms of transport links, this can be illustrated schematically as shown in Figure 19.

The DCC’s vision broadly sees suburban hubs and the city centre linked by a public transport network, and sees most residential development occurring within a 10-minute walk of an existing hub or high frequency bus route. This means that most people would live close enough to their local centre to be able to walk or cycle to it, and that from there, they could either join the Strategic Cycle Network and cycle to other hubs or the city centre, or they could access the public transport network, which again would link them to key destinations.

This Strategy focusses on how transport, particularly active modes and public transport, can better support thriving centres. This approach will enable people to choose modes of travel other than the private car, with benefits for health, amenity, community, the environment and increasing resilience to rising fuel prices. Undertaking journeys by private car is still expected to be desirable for the foreseeable future, and the transport network’s ability to support car travel will continue to be maintained. The strategic approach will be as follows.

Integrating land use and transport planning – supporting the Spatial Plan’s vision

The Spatial Plan seeks to maintain a vibrant central city supported by a hierarchy of suburban and rural centres that are social and economic hubs for local communities with quality built form and a high quality public realm. Ensuring high pedestrian amenity and safety in centres requires management of public car parking and activities that generate high levels of vehicle movements.

The Spatial Plan promotes more mixed-use residential development in the central city and suburban centres and residential intensification particularly in areas with high levels of accessibility to larger centres and well-serviced public transport routes. The key method for achieving this is the Dunedin City District Plan, which establishes objectives, policies and rules guiding the type of land use activity that can occur in different parts of the city. The District Plan (under review as at 2013) will be reviewed to give effect to the Spatial Plan’s aim of more medium-density housing and residential infill. This will help support local services and mean that more people live within an easy walking distance of a centre and other key destinations. Provision of local services (such as shops and health centres) close to where people live reduces the need to travel long distances, benefiting the local economy and increasing people’s disposable income, as less is spent on travel. In 2011, 39% of the residential units in Dunedin’s residential zones were within 400m of a local activity centre (approximately 5 to 10-minute walk) and 68% were within 800m (approximately 10 to 20 minute walk)42.

Figure 19. Schematic illustration of compact city with integrated network of hubs and centres, connected by walking, cycling and public transport. Illustration assumes underlying road connections maintained for vehicular use.

Figure 19. Schematic illustration of compact city with integrated network of hubs and centres, connected by walking, cycling and public transport. Illustration assumes underlying road connections maintained for vehicular use.

The Dunedin Digital Strategy

Improved broadband networks that enable people to work from home or attend meetings via teleconferencing also have the potential to help reduce people’s need to travel. The Dunedin Digital Strategy aims for high-speed broadband and WiFi to be extended to most of Dunedin’s residents, in both urban and rural areas, by 201643. This improved access to the internet can benefit everyone, but may be of particular benefit to those without access to a motor vehicle. This is approximately 10% of Dunedin households on average, but this figure is higher in some areas (see Figure 11 in Section 2.12).

Centres Programme

The Spatial Plan intends that local centres become thriving hubs of activity, supporting the provision of goods and services. To support this goal, and at the same time improve safety in local centres, a Centres Programme will be developed. The aim of the Centres Programme is to ensure Dunedin’s local centres are great places for people, in terms of traffic safety, accessibility and amenity, particularly by giving pedestrians increased priority within each centre.

To achieve this, each local centre has been assessed for safety and accessibility, to help identify those centres with the most serious problems that need to be prioritised for early action. The centres have been split into two categories – major upgrade and minor upgrade. Funding for these centre upgrades will be obtained from existing operational budgets where possible. However, the magnitude of improvements in some larger centres exceeds the scope of existing budgets, and separate funding will need to be secured. As illustrated previously in Figure 13, the central city area has by far the most serious safety problems, and this is prioritised as the first centre requiring a major upgrade.

Centres upgrades will also include improvements to key designated strategic walking routes within a 10-minute walking distance of each centre. Requests for improvements to footpaths will be prioritised according to whether they are on designated walking routes and their level of risk. Where possible, these improvements will be made as part of existing programmes.

City Centre

Through this Strategy the DCC proposes to undertake a major upgrade of the transport system in the central city area,with a focus on safety and accessibility. A concept will be developed that draws on previous work, such as the DCC’s Central City Plan, as well as analysis of crash data and accessibility problems. The aim would be to significantly improve the pedestrian priority within the central city, to support a thriving city centre where people want to spend time, socialise, shop and do business.

In order for this to work it will be necessary to reduce the amount of through traffic in some parts of the central city and support better access to the central city as a destination for all users. Reducing the amount of through traffic in the central city will only work if adequate alternative routes are provided. To achieve this it would be necessary to include enhancement of existing bypass corridors to the east and west of the CBD, to provide for freight and arterial traffic. This approach will not only improve the vitality and safety of the central city, but also benefit motorists who will experience fewer delays.

Mosgiel

A major safety and accessibility upgrade is also being proposed for the Mosgiel town centre. As with the Central City, the aim of the Mosgiel Town Centre upgrade will be to improve safety and accessibility, particularly for vulnerable users, to ensure the vitality and prosperity of the Mosgiel shopping area. Providing for vulnerable users is particularly important in Mosgiel as there is a high proportion of elderly residents and young people, who are especially dependent on good pedestrian and cycling facilities and high levels of mobility access.

The key areas to be addressed in Mosgiel will be identified through consultation with the community, but are likely to focus on Gordon Road, Factory Road and the Gordon Road – Factory Road intersection. There is an opportunity to significantly improve the heart of Mosgiel for residents and businesses, and create a thriving social and economic hub. Gordon Road is State Highway 87, and is administered by the NZTA. Any project to upgrade the Mosgiel town centre will therefore involve a collaborative approach.

Major centre upgrades

As mentioned above, several of Dunedin’s other local centres have also been identified as in need of major safety and accessibility upgrades. These include:

- South Dunedin

- Gardens (North East Valley)

- Caversham

- Mornington

- Green Island

- North Dunedin

Concepts will be developed for each of these centres in consultation with the community as they come up on the Centres Programme. Where other non-transport works are also planned for a centre (such as urban streetscape and amenity upgrades, or sub-surface utility maintenance), the DCC will co-ordinate with other agencies and the community to ensure opportunities for integrated delivery are maximised. Those remaining centres not requiring a major upgrade will be improved over time through minor targeted improvements carried out through existing budgets and work programmes.

Safe speed in centres – integrating design speed and speed limit

As discussed in the Focus on Safety (Section 9.1), the highest concentration of vulnerable user activity occurs in local centres and traffic speed needs to be managed in a manner appropriate for the mix of uses and activities that take place in those centres. Accordingly, the DCC has recognised that 50km/h traffic speed is too fast for local centres. This has been recognised at a national level, through the Safer Journeys strategy and a review is currently underway to establish new national policy on appropriate speeds. The DCC will work toward a top traffic speed of 30km/h in local centres while remaining flexible as new national guidance takes shape. The DCC will review the appropriate desired speed for local centres in Dunedin as part of any review of this Transport Strategy.

To achieve lower speeds in centres, it will generally be necessary to implement a lower speed limit in conjunction with redesign of the road environment (based on the consideration of ‘design speed’ (discussed in Section 9.1)44. When lower speed limits are implemented, lower design speeds will typically need to be achieved through traffic calming measures, urban design and amenity features and improved provision for pedestrians, cyclists and mobility impaired users.

Reduction in speeds within centres will have the added benefit of making centres more accessible, pleasant places where people will want to spend time, which will have economic benefits for businesses. The DCC will achieve lower speeds in centres through the implementation of the Centres Programme, described above.

Car parking

Car parking has both positive and negative effects. Provision of parking in the central city and other local centres is an important way of providing access and supporting the economic activities occurring in the centre. As the private car is by far the most common mode of travel for Dunedin residents at the moment, it is important to provide the appropriate level and type of parking to support car access to these areas. However, provision of parking in centres is primarily on-street, which often conflicts with other activities in the centre, such as pedestrian movement, public transport and general street scape and amenity. The traffic movement generated by parking also has negative effects in terms of pollution and safety problems. This tension has been described as “a real dilemma between the individual’s desire to own and park a car and the collective desire to enjoy a safe and attractive street”45. The availability and cost of parking is also a key driver in whether people prefer to drive over using other travel modes46.

All of Dunedin’s on-street parking is controlled by the DCC, while off-street parking is provided by DCC and private operators (in surface level car parks and parking buildings). Aside from public casual parking, there are also District Plan requirements for businesses in certain zones to provide staff and customer parking, and in some residential zones, owners are required to supply a ratio of car parks per bedroom. The requirement for, and provision of, parking needs to be carefully managed in an integrated way to ensure appropriate access to goods and services is provided, urban amenity is maintained, unproductive use of real estate is minimised, road safety is improved and non-car travel modes can be adequately and safely provided for. Achieving an appropriate balance between these considerations is complex and in Dunedin, disproportionate priority has traditionally been given to low-cost on-street car parking. Under this Strategy, the DCC’s approach will be to increasingly redress this imbalance.

The DCC will develop a Parking Management Policy that will sit under this Strategy and give effect to the vision and objectives of this Strategy.

Parking in the central city and centres

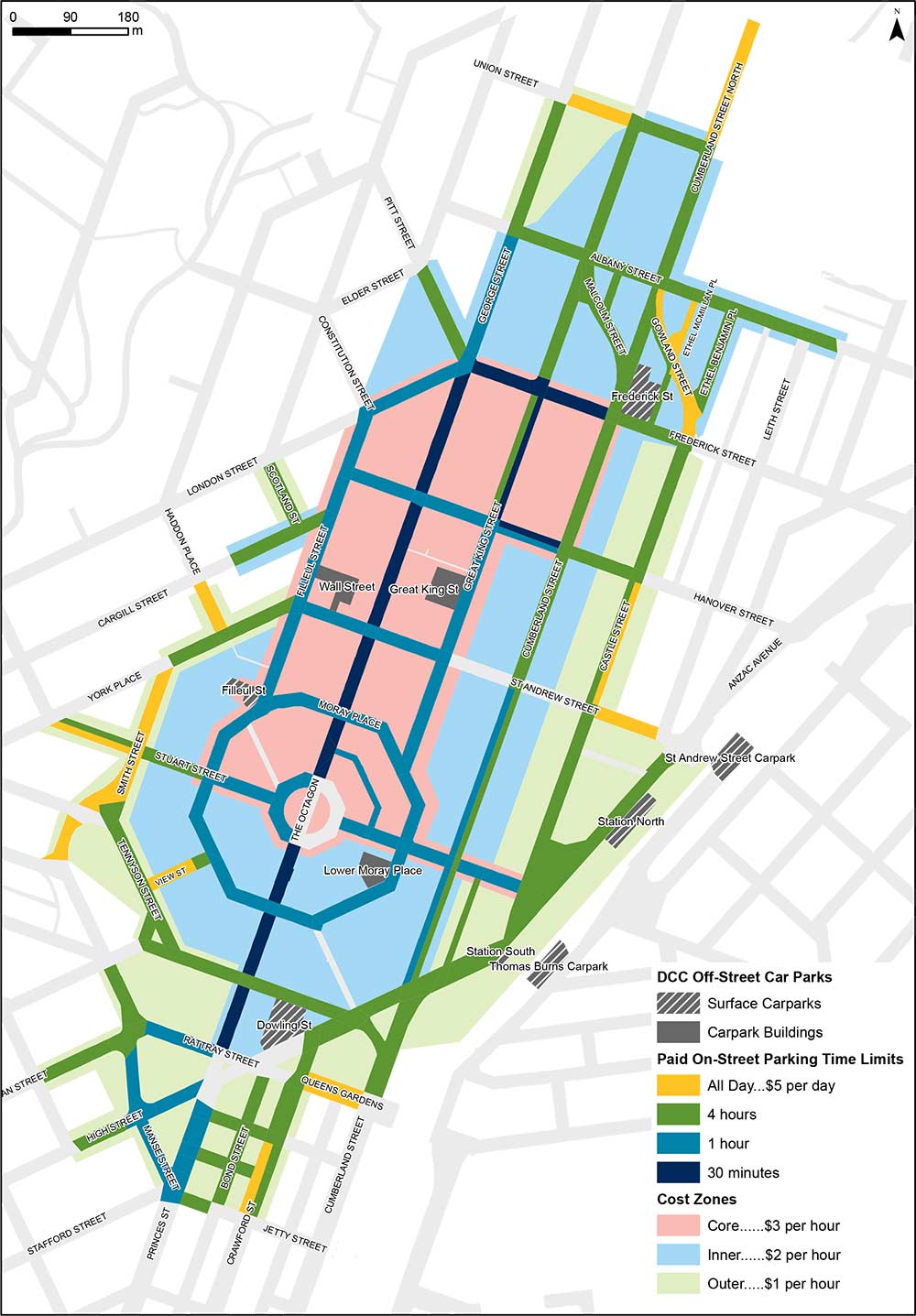

The DCC carries out a central city parking survey every 5 years, to monitor and review the provision of parking in the central city. This survey, last carried out by an independent consultant in 2012, found:

- Overall parking in Central Dunedin is well managed.

- Parking restrictions radiate out from the Core Central City in a logical manner from Paid P30 along George Street to commuter parking provided in the Outer Central City.

- Paid P60 parking in the Central City was inconsistent with the demand in the areas it is provided and therefore it may be appropriate to change Paid P60 parking to Paid P120 parking.

- There is also scope to alter how Paid P240 parking is distributed in the Central City.

- Even at peak times 20% of the parking spaces in the central city area are vacant.

The current paid parking area is shown in Figure 20.

In some local centres parking is in high demand. In these centres parking will be managed by taking an area-based approach to provision of parking. To support the Spatial Plan vision, and this Strategy’s aim of increased safety, travel choice and more vibrant centres, there will be a move towards provision of parking on the peripheries of the centre, with less on-street parking overall and a shift toward a higher proportion of parking provided in off-street car parks.

Until the Parking Management Policy is adopted by the Council, the DCC’s 2009 Parking Strategy will remain operative.

Figure 20. Central City Paid Parking Area

Figure 20. Central City Paid Parking Area

Footnotes

- As at 2011

- Dunedin Digital Strategy

- Roslyn is currently Dunedin’s only local centre with a design speed close to 30km/h.

- English Partnerships (2006) Car Parking: What works where? English Partnerships National Regeneration Agency. p.4.

- Shoup, D. (2011) The High Cost of Free Parking. American Planning Association. Chicago.