Problem

Freight movement is vital for Dunedin’s economic and social wellbeing. Dunedin is also a key freight hub for the wider region. Freight needs to be able to move efficiently and effectively to and from Port Otago, and through the city, without adversely affecting the safety and amenity of the city53.

Strategic response

Encourage increased use of the rail network for freight movement and provide safe and efficient access for freight vehicles on designated routes.

Benefits

- Increased proportion of freight being moved on the rail network.

- Efficiency of freight movement on designated freight routes is maintained, and appropriate access is provided to support local economic activity.

Goal

A significantly increased proportion of the total freight load that passes through Dunedin will be being transported by rail by 2024.

Strategic approach

The DCC has expressed its commitment to ensuring Dunedin is an economically productive and sustainable city in the Economic Development Strategy (outlined in Section 1.4.2) and the Community Outcome ‘A thriving and diverse economy’, set out in the Long Term Plan. The EDS emphasises the need for a transport system that provides access to export opportunities. Freight movement is central to exporting; it is also the way we bring the various goods we rely on into the city. The safe and efficient movement of freight is a key part of this.

The Dunedin community has expressed a wish to see better connections in and out of Dunedin, including improved rail services in Dunedin and more use of rail for freight movement54. The RLTS also asserts the important role rail plays in regional freight movement up and down the East Coast and to Port Otago55.

While this Strategy focusses on increasing the role of rail, it is important to acknowledge that trucks will continue to be an integral and important component of Dunedin’s transport system for the foreseeable future. Even as more emphasis is placed on increasing the use of rail for freight, there will continue to be a need for trucks to transport freight around the region. Trucks will be required to move freight from its origin (such as transporting logs from forests, or agricultural produce from farms) to where it can be transferred to rail. Trucks (of varying sizes) are also critical for the distribution of goods within urban areas and to communities that cannot be served by rail. The current central Government direction is also promoting an increase in the number of High Productivity Motor vehicles (HPMVs), which are essentially large trucks carrying heavier freight loads. The stated aim of the government’s push for HPMVs is to see “more freight carried on fewer trucks”56.

Providing appropriate support for freight movement by both road and rail is important. The strategic approach for achieving this will be as follows.

Freight and road safety

Under the ‘principle of homogenous use’ (explained under ‘Focus on Safety’, Section 9.1), large heavy vehicles, such as trucks used for moving freight, cannot mix safely with vulnerable road users. The DCC acknowledges the need for efficient freight movement, but if Dunedin is to become one of the world’s great small cities, this cannot be achieved at the expense of safety. Ensuring efficient and safe movement of freight will require prioritising certain routes for freight where appropriate, separating freight traffic from vulnerable users, and controlling vehicle speeds where separation cannot be achieved and mixing is inevitable. It can also mean removing freight from the road network and onto other modes such as rail and coastal shipping.

Increased use of rail for freight

The Dunedin community has a strong desire to see a greater proportion of the city’s freight being transported by rail. This was a strong theme that came through the Your City, Our Future consultation in 201157. The DCC will work collaboratively with KiwiRail, Taieri Gorge Railway, the freight sector, primary production companies and other exporters, as well as with the ORC and NZTA, to encourage greater use of rail. This will support the local and regional export economy while also improving safety by reducing the proportion of heavy freight vehicles travelling through the central city and interacting with high proportion of vulnerable road users. Supporting greater use of rail is also consistent with the RLTS58.

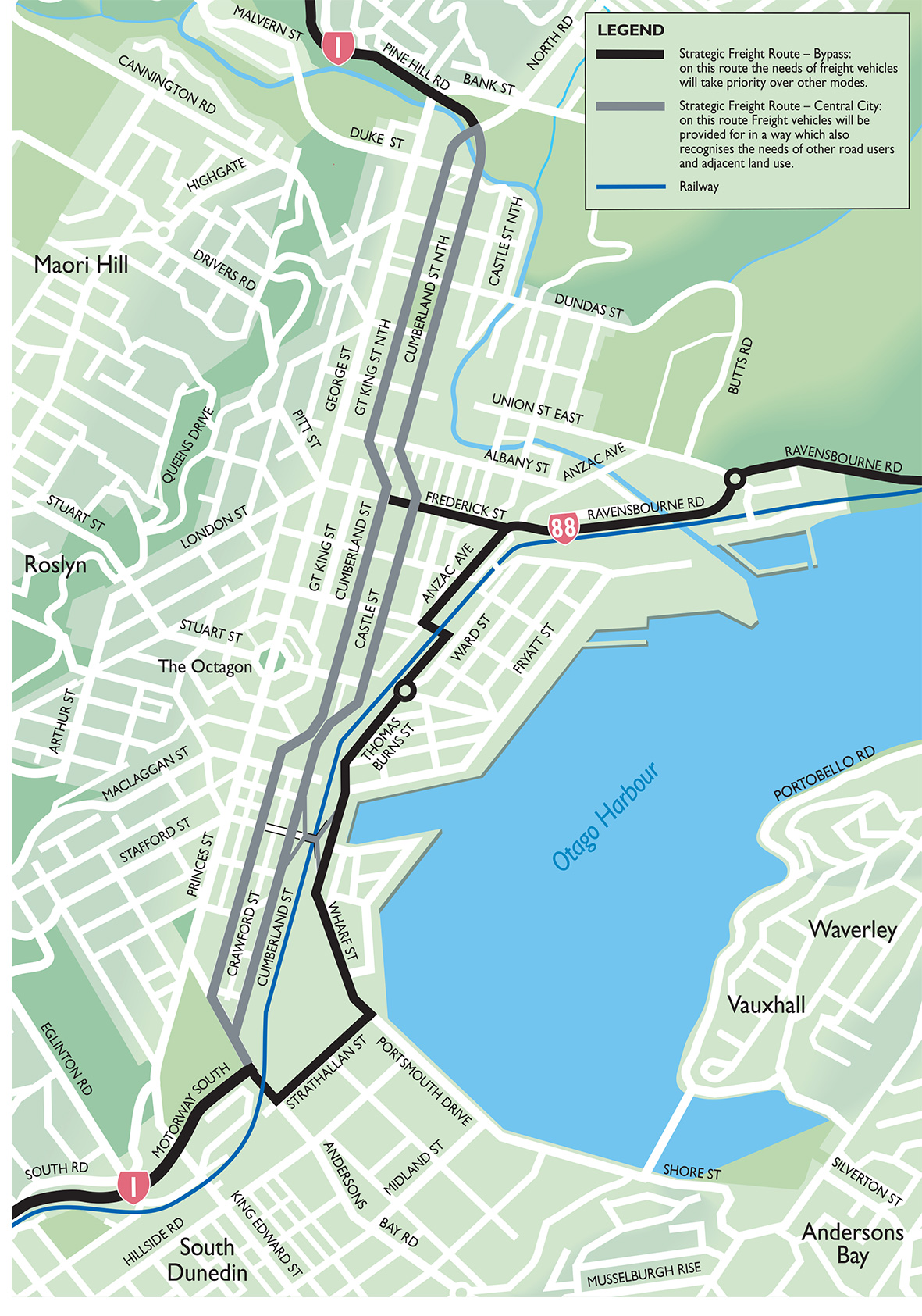

Strategic freight routes and by-passes

Where freight needs to travel by road, the DCC will promote and provide for the separation of heavy freight vehicles and vulnerable users through designated heavy freight corridors and bypasses. The strategic freight routes are shown in Figure 23 at right. On the Strategic Freight Bypass, the DCC will prioritise safe and efficient freight movement over other transport modes. On the Strategic Freight Route – Central City (the 1-way pair) it may not be safe or desirable to give freight vehicles full priority over other modes, however, due to a lack of other options, it is still important to provide for safe and efficient freight movement on this corridor. Therefore, on the Central City Strategic Freight Route, safe and efficient freight movement will be provided for in a manner that recognises the importance of other modes and land-uses along the corridor. Possible means of achieving this could include giving freight higher priority at times of day when there is less likely to be conflict with other priority users of those routes, speed management, parking management and limiting access along the corridor.

Figure 24a. Indicative High Productivity Motor Vehicle and over-dimension routes – Southern and Taieri

Figure 24a. Indicative High Productivity Motor Vehicle and over-dimension routes – Southern and Taieri

High Productivity Motor Vehicles and over-dimension vehicles

High Productivity Motor Vehicles (HPMV) are trucks that exceed the weight (44 tonnes) or length of a vehicle that is allowed to use any road as of right. HPMVs can only operate under permit from the Road Controlling Authority (RCA) (i.e. NZTA and/or the relevant council), and only on roads and bridges that are specified on the permit as being able to accommodate the weight and length of the HPMV59. HPMVs were made possible by changes to transport regulations in 201060.

Recent rises in fuel costs, increasing pressure for greater efficiencies across the transport sector and a central Government focus on economic growth and productivity have all been key drivers of the move to provide for these larger vehicles and the NZTA is supporting this direction through its ‘more freight on fewer trucks’ approach61. Dunedin can expect to see an increase in the number of HPMVs using the road network in the coming years.

Because heavier vehicles have a greater effect on roading infrastructure, and longer vehicles have different cornering space requirements, it is not economically feasible to provide for all types of HPMV everywhere on the network. Under the ‘principle of homogenous use’ discussed in Section 9.1, there are also safety implications with larger and heavier vehicles in areas with high vulnerable user activity. Therefore, it is necessary to take a strategic approach to providing for HPMV in order to maximise the benefits they bring and to minimise the costs or safety effects.

There are two broad categories of HPMV: 50MAX (standard dimension trucks with an additional axle allowing them to be loaded up to 50 tonnes), and all other HPMVs. These will each be provided for through the following approaches.

50MAX:NZTA will be responsible for granting permits for 50MAX vehicles across the entire road network (local roads and state highways). Under a 50MAX permit, vehicles will have access to all areas on the network, unless expressly stated on the permit (or sign posted on a route by the road controlling authority). NZTA will work in partnership with the DCC in allocating 50MAX permits and the DCC may request that NZTA exclude certain structures or sites from 50MAX permits where infrastructure is deemed inadequate to bear the total weight of a 50MAX vehicle.

Figure24b. Indicative High Productivity Motor Vehicle and over-dimension routes – Central and Port

Figure24b. Indicative High Productivity Motor Vehicle and over-dimension routes – Central and Port

Other HPMV: The DCC will grant permits for all non-50MAX HPMVs on a case-by-case basis. The DCC has assessed and identified certain routes as indicative HPMV routes and maintains these routes to a higher standard to accommodate such vehicles, as shown in Figure 24a and Figure 24b.

The DCC has also designated a number of routes for over-dimension traffic. Over-dimension vehicles are those which exceed the standard regulations for width, length and/or height and therefore cannot access all parts of the network. The current over-dimension routes are also shown in Figures 24a and 24b. The need to maintain sufficient space on over-dimension routes imposes limits on the type of development, streetscape works, and traffic calming measures that can be done on that route. For example, plantings over a certain height will not be possible as they would prevent the through movement of wide vehicles, and poles may need to have hinged bases. This has an effect on amenity and safety where over-dimension routes pass through busy areas or centres.

It is also important that there are alternative routes available for over-dimension vehicles in the event that a key route inaccessible. It is therefore vital that the appropriate routes are designated for over-dimension vehicles and protected from inappropriate development as any one obstruction may affect the entire route. The DCC will review the over-dimension routes, in consultation with the community and heavy haulage industry, to identify whether improvements can be made to meet the needs of the heavy haulage industry while allowing for safety and amenity improvements to centres.

Identifying indicative preferred HPMV routes and rationalising over-dimension routes will allow the DCC to prioritise investment toward upkeep of key infrastructure on these strategic routes and to protect them from inappropriate development.

Table 3. Level of Service for vehicles on the road network.

| Level | Flow | Intersection Delay |

|---|---|---|

| A | Free Flow | 0 – 12 seconds |

| B | Stable Flow | 0 – 12 seconds |

| C | Stable Flow | 13 – 19 seconds |

| D | High Density but Stable Flow | 19 – 25 seconds |

| E | Unstable Flow Nearing Capacity | 25 – 50 seconds |

| F | Forced Flow with Queues | 50 seconds+ |

Freight and congestion

As shown in Figure 25, there are very few parts of Dunedin’s transport network that suffer from serious congestion. Modelling projections to 2041 also show that Dunedin is not predicted to suffer from serious congestion within the life of this Strategy. Congestion can have a safety benefit in that it generally leads to speed reductions, and can also encourage people to move away from single-occupant car use toward other modes of transport.

However, where congestion causes inefficient freight movement it hinders economic productivity and affects access to export opportunities. Building new roads or adding lanes to increase road capacity is costly and often results in increased traffic volumes, in turn requiring more investment to increase road capacity and creating a costly cycle of on-going expenditure. This cycle also reduces amenity and can have a negative effect on surrounding land use as larger roads with more traffic begin to dominate some areas.

The DCC will accept congestion up to Level of Service E at peak and off-peak times (see Table 3 for definitions). but will prioritise measures to improve efficiency for freight vehicles on designated freight routes. When and where congestion does need to be addressed on freight routes, the DCC will do so according to the Transport Investment Hierarchy (outlined in Principle 1, Section 8).

Inland Port

One way of integrating road freight and the rail network is to provide for the transfer of goods from between road and rail through an ‘inland port’. Some development of an inland port has taken place at the Taieri Industrial Estate (North Taieri), where Fonterra has developed rail sidings to enable transfer of dairy products between truck and train. There may be potential to develop this as a more fully functional inland port, supporting a range of freight to and from the wider Otago and Southland regions. Freight coming by truck from the hinterland could be transferred to rail for the final stage of its journey to the port, or to continue its journey north or south, while freight entering Otago through Port Otago or from the main trunk railway could be taken by rail to this inland port to be transferred to truck for local and regional distribution.

There may also be merit in investigating future development of inland port facilities to the north of Dunedin. In the event that a greater proportion of the freight load from the mid-South Island (such as from the Canterbury area and further afield) begins to pass through Port Otago the case for an inland port north of Dunedin would increase. The DCC supports the concept of an inland port as an effective means of providing for freight while reducing the negative effects of heavy vehicles on road safety and urban amenity. The DCC will work collaboratively with KiwiRail, ORC, NZTA, primary production industries and other importers and exporters, toward investigating the feasibility and merit of further developing an inland port at North Taieri and the possible benefits of developing a facility north of Dunedin at some point in the future. In keeping with the RLTS, the DCC will also support this through appropriate provisions in the District Plan.

Figure25. Projected levels of service (areas of congestion) on Dunedin’s network in 2041.

Figure25. Projected levels of service (areas of congestion) on Dunedin’s network in 2041.

Urban freight delivery

While Dunedin does not currently experience major problems associated with urban freight delivery, it is possible that this may become a challenge over the lifetime of this Strategy. As traffic volumes increase, urban freight delivery becomes both a contributor to and victim of the growing congestion in urban areas that exposes the population to noise, pollution and nuisance. Many solutions to these issues have been developed in larger cities around the world62.

The DCC will monitor the urban freight delivery situation in the central city and other centres, and work with the community and stakeholders to develop appropriate solutions as issues arise. Future possibilities include developing urban distribution centres and implementing time restrictions on goods deliveries in critical areas. A distribution centre operates similarly to an inland port, but is a depot where goods originating from or destined for urban areas (such as consumer goods for shops), can be transferred from larger long-haul trucks or rail, to smaller vehicles more suited to interacting with the range of users in urban areas.

Footnotes

- In this Strategy, the term freight is used generically to include all freight, forestry, agricultural produce and all other bulk goods, see glossary.

- Your City, Our Future consultation 2011

- RLTS, Output 3.3, p.32.

- NZTA (2013) Vehicle Dimensions and Mass: Moving more freight on fewer trucks – the NZTA’s new priority. Newsletter, June 2013.

- Your City, Our Future 2011

- RLTS, Output 3.3, p. 32

- HPMVs are no higher or wider than standard trucks. See: NZTA Vehicle Dimensions and Mass Newsletter, Issue 12, June 2013. www.nzta.govt.nz/resources/vdam-rule-implementation

- Land Transport Rule: Dimensions and Mass

- NZTA Vehicle Dimensions and Mass Newsletter, Issue 12, June 2013. www.nzta.govt.nz/resources/vdam-rule-implementation

- European Commission (2008) Freight Intelligent Delivery of Goods in European Urban Spaces.