Understanding our natural environment – and how it’s changing

We are studying how South Dunedin is being impacted by changes in weather, sea level, and groundwater level, and what we can expect over the coming decades. We want to explain the science behind the natural hazards in South Dunedin, like flooding, and climate change.

This information has been compiled by the natural hazards team at the Otago Regional Council, in conjunction with a range of leading scientists.

Read on to get informed and get involved!

Reading about these hazards can be scary

But it is important to know what our challenges are, so we can talk about how to respond and make the best plan.

If we do this together we can make South Dunedin a safer and better place to be.

Rain and more rain | Flooding

More rain events are expected in the future because of climate change. Yearly rainfall could be up by 6% by the century’s end.

Intense rainfall already causes problems in South Dunedin. We have all seen what can happen when we get a decent downpour.

Many of us will remember June 2015, when a deluge of 142mm rain in 24 hours triggered a major flood. The aftermath included slips, knee-deep floods, debris-strewn suburbs, home damage, and water contamination. Heavy rainfall events like this one are likely to become more regular in the future.

-

Why is there a flooding hazard in South Dunedin?

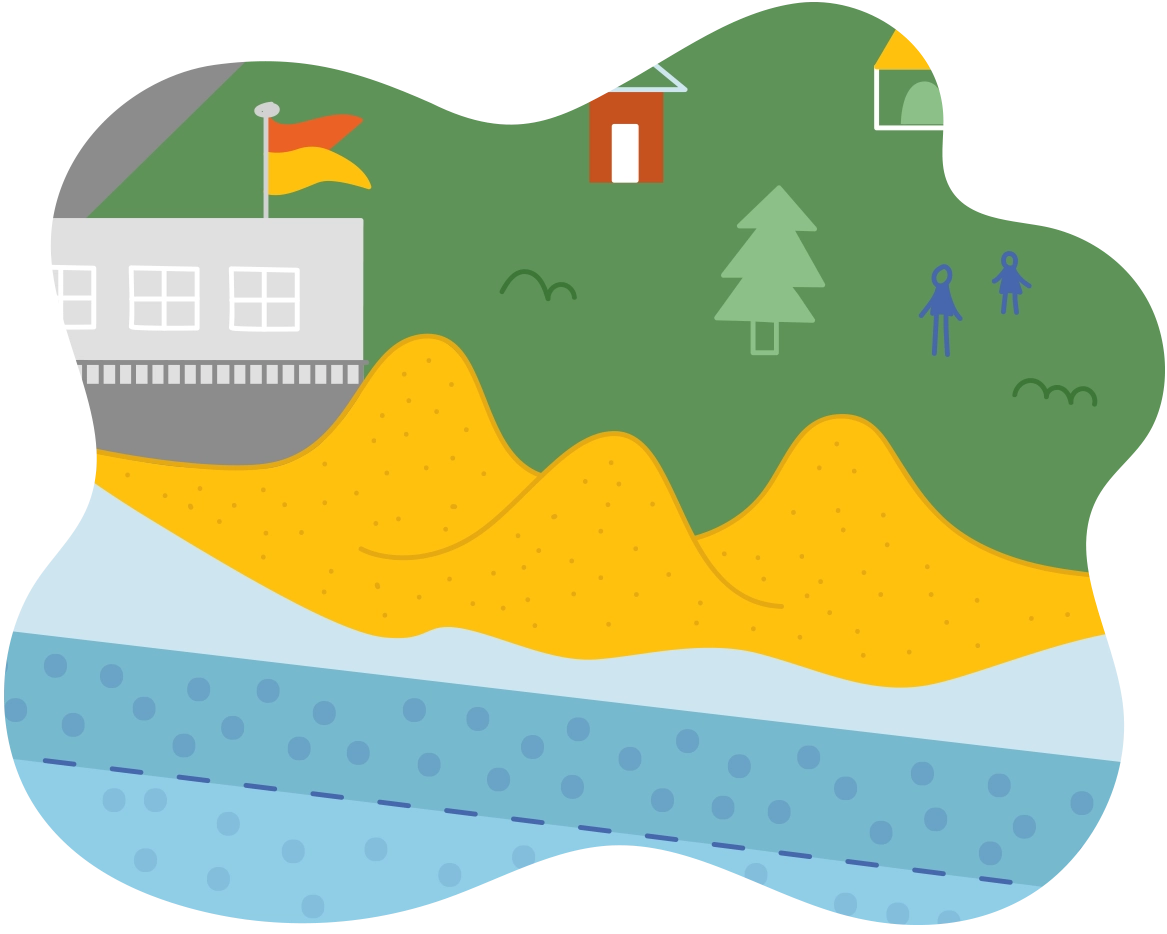

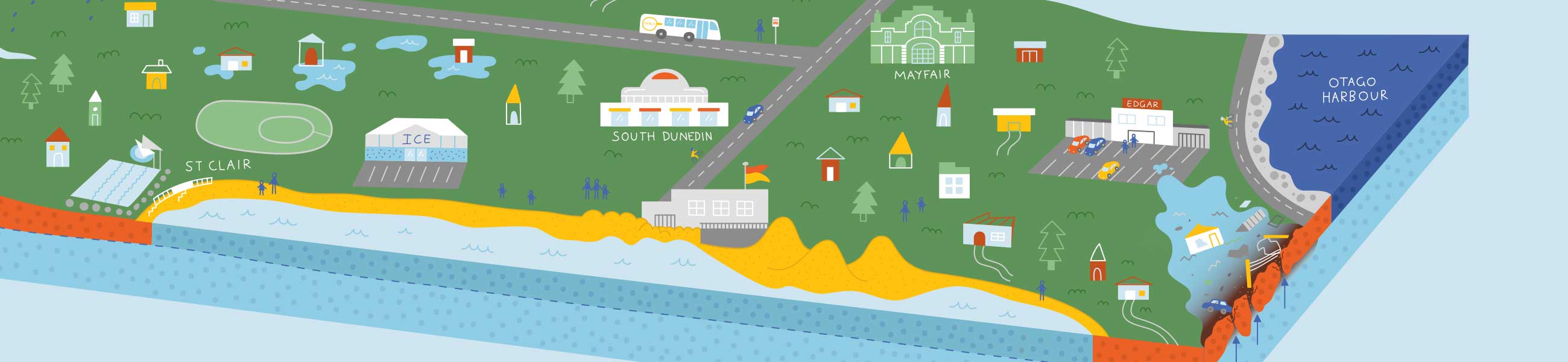

South Dunedin sits at the bottom of a large urbanised basin, with no natural way for the water to flow out to sea. All the hard work is done by pipes and pumps and that will be a tough job with all the extra water coming our way in the future, from the ground, sea and sky.

The groundwater is already close to the surface and this plus all the rain means South Dunedin experiences a lot of surface runoff. Future sea-level rise is expected to worsen flooding.

Puddles and Ponding | Groundwater rising

A shallow groundwater table can result in soggy soil and puddles in low-lying areas. Houses can become damp and sections waterlogged.

The groundwater table is shallow, as little as 30cm below the surface in some places. Rising sea levels will likely push the groundwater up even further, leaving less room in the ground for rain to soak in and resulting in more surface flooding.

-

Why is there a groundwater hazard in South Dunedin?

When it rains, water can soak into the ground and fill the cracks and spaces between the soil, sand, and rock. We call this groundwater. The upper limit of groundwater is called the water table, and its level changes with the seasons and rises when it rains. Close to rivers and the sea, the water table also changes along with the tides.

The original wetland had groundwater right to the surface. Reclamation since the 1870s has raised South Dunedin ground levels only a little above the water table. As a result, South Dunedin is at risk of flooding, ponding, and increasing, ongoing damp, due to a shallow water table that is likely to rise.

Land ups and downs | Movement and liquefaction

The level of the ground can change up or down slowly due to gradual movement, or suddenly due to an earthquake. Preliminary satellite data suggests parts of South Dunedin are sinking very slowly, at about half a millimetre per year. More years of surveying should provide a clearer picture.

During earthquakes, underground layers of wet soil can act like a liquid, and ooze out of the surface, along with lots of water. The soil can't support the weight above, and this can buckle roads, crack pipes and badly damage buildings.

-

Why is there an earthquake hazard in South Dunedin?

When settlers began reclaiming the land in the 1870s, they filled in and topped up wet, low areas with materials from the coastal dunes. South Dunedin is sitting on land that mostly consists of soft, sandy sediment. Several geological faults in the Ōtepoti Dunedin area could cause large earthquakes. Sediment-filled basins such as the broader South Dunedin area can face greater earthquake shaking and can cause liquefaction – where thick watery mud comes up through cracks to the surface, and land subsidence – where the land slowly or suddenly sinks.

Coastal erosion | Sea level rise

The sea level is expected to rise by 19 to 27cm by 2050. By the end of the century the sea level is expected to be 40 to 85cm higher than today’s levels.

Beaches and dunes can be broken down and worn away by destructive waves, high winds, storm surges and sea level rise. This could also expose an old landfill under Kettle Park.

-

Why is there a coastal hazard in South Dunedin?

Being so close to the ocean and so close to the high-tide mark puts the community at risk of coastal hazards. These hazards can be gradual, for example sea-level rise and coastal erosion, or event-based, for example storm surges and tsunamis.

When South Dunedin was reclaimed and settled around 150 years ago, many houses were built below the high tide mark at the time. Today, most of the area is no more than 50cm above high tide. Sand dunes, like the ones in St Kilda and St Clair, help protect South Dunedin against water coming in from the sea. Unfortunately, these soft, sandy beaches are sensitive to environmental changes and from human interference. The St Kilda and St Clair dune systems are already showing signs of coastal erosion and movement inland.